By David Boas

The following article was published on May 2, 2019 in the Jerusalem Post. Courtesy of Jerusalem Post.

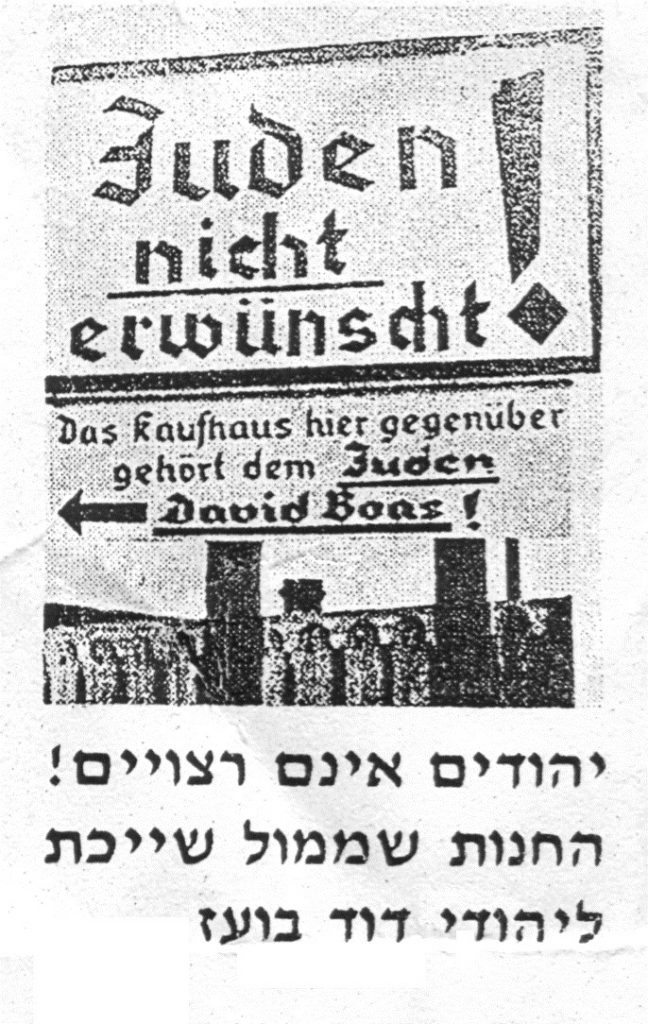

Pictured above: The Boas family house in Bad Harzburg, Germany 1933

On my personal Holocaust Memorial Day, I admire my father and his brother, who chose to leave Germany and start a new life in Eretz Yisrael. On my personal Holocaust Memorial Day, I remember standing in front of an audience in Hamburg, telling them what I think of the atrocities performed by the German people, with a large photo of my family behind me. This may not be victory, but it was the least I could do in memory of my murdered family.

David Boas, May 2019

The personal histories of the second or third generation of Holocaust victims’ descendants often start with a description of the doubts they have had before embarking on telling their story, for fear of touching a sore spot, opening up old wounds and bringing to the surface lurking anxieties that have been suppressed for decades.

Another characteristic of nearly every personal history that involves the Holocaust is being able to overcome the reluctance to dig into the horrors of the past and break the prolonged silence conspiracy. In many ways, my story is similar, yet different.

It starts with trips I used to make regularly to a computer and software trade show held in Hannover, Germany. In one of my visits, approximately a decade ago, I was suddenly seized by a feeling of missing out: I was only 75 minutes away by train from the town in which my father grew up and which I never dared visit.

The next day found me disembarking on the train at the Bad-Harzburg station. When I asked where the local synagogue was located, the information clerk replied with a mix of confusion and suspicion, “There is no synagogue here, sir,” she said. In response to her question, I told her I am from Israel, that my father grew up in the town, that his parents had owned an apparel and shoe store and that I would like to find out more about the family and the house. In attempt to help me, perhaps even get rid of me, the clerk referred me to the manager of the municipal library.

Surprised and intrigued by my story, the library manager hurried to locate the census books of the town from the beginning of the 1930’s. Among others, these volumes included the telephone directory of those days. We easily located the address and 3-digit (294) telephone number of the Boas Family.

The names of the family members and paid staff that lived in the same household were listed below. These included the housekeeper, a hunter, a locksmith and maintenance workers. As of 1937, the Boas family name ceased to appear and was replaced by the name of one of the store workers who had bought the house later, in 1939, as part of “Arization,” a law that forced Jews to sell their properties to Arian citizens (“Zwangs Verkauf”).

The library manager arranged a meeting for me with the editor of the local newspaper, Ms. Rosie Schwartz. She, too, was excited about my personal story and both of us set to take out large and heavy volumes of the Gosslariche Zeitung from the 1920’s and 1930’s. There, we found advertisements of my grandparents’ store, which was called Bazar D. Boas and was inaugurated in 1920. In 1930, the store held special promotions on its 10th anniversary.

Ms. Schwartz referred me to Dr. Kurt Neumann, a man nearly 80 years old and the town’s historiographer. A few years ago, he had authored the Town’s History Book, which mentions my father’s family, among others.

Dr. Neumann told me that, as of the beginning of the 1930’s, the town became one of the command posts of the National Socialist Movement. “Here, in this square,” Dr. Neumann showed me, “Hitler and Goebbels held one of their first election assemblies of the Nazis.” In 1930, he added, a big march was held in honor of the Harzburgerische front, an important initiative of the young Nazi movement. Youth dressed in brown uniform marched throughout the town and Adolph Hitler greeted them in person at the city gate. Note that the march took place three years before Hitler’s rise to power. During that visit, Dr. Neumann also arranged for me to meet with the mayor, who, similar to many Germans, hurried to assure me he was a small child during the “shocking and horrific” Holocaust. He added that, as a local, he remembers the good reputation my family had for its generosity and donations to the needy.

A SPECIAL BOND

Approximately one year after my visit to the town, I learned that an entry in the Holocaust Encyclopedia (publisher: Yad Vashem) includes a billboard poster from 1938, which announced that Jews were unwanted and that the store across the street belonged to the “Jew David Boas.” Some years later, I saw this exact poster in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

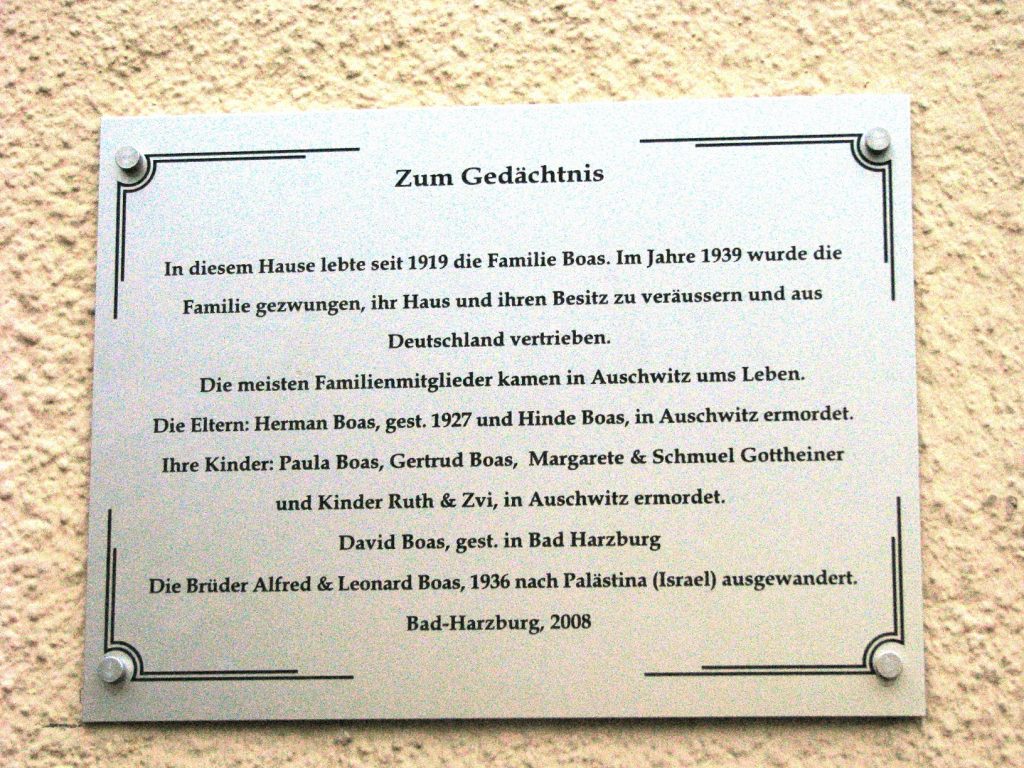

I visited the town a few times more. In November 2008, on the anniversary of Kristal Nacht (Night of Broken Glass), our family came with the idea of commemorating our family with a memorial plaque on the wall of the family home in Harzburg.

We needed to obtain the consent of the current owners of the house. The owner was a lady named Ms. Wede, who inherited it from her mother, who bought it in 1969 from the person who bought the house from my family during the “forced property sale.” Dr. Neumann located Ms. Weda, but was unable to obtain her consent. I decided to approach her directly.

During my telephone conversation with her, I made it clear that I had no intention of claiming the house from her and that I only wanted to perpetuate the memory of my family with a modest memorial plaque. I made it clear that, if she declines my request, I would do nothing against her will, but, if she agrees, she would be doing a very good deed. Serval days later, Ms. Wede called to tell me she agreed.

It snowed heavily on November 8, 2008, but a small group of people convened, nonetheless, next to 17 Dr. Heinrich Jasper Street, corner of Unter den Linden. The group included my wife, two of my three sons, one of our daughters-in-law, my cousin with his wife and daughter, the mayor, Mr. Peter Abrahams, the editor of the local newspaper (now retired), Ms. Rosie Schwartz, a couple of friends from Hannover, Ernie and Marcelle Sixtus, a photographer and writer of the local newspaper, the house owner, Ms. Wede, and, of course, Dr. Kurt Neumann and his wife, who were honored with unveiling the plaque.

A month after the ceremony, I received an e-mail from an anonymous woman from Hamburg. She wrote me that she had read the stirring article about the memorial plaque and that she had more information about my family. This is how I became acquainted with this wonderful woman, Sabine Brunotte. As the years went by, we developed a very special bond.

Sabine was a social worker who volunteered at Hamburg’s central archive, out of a personal mission to “repent and be redeemed” for the sake of the families of the Holocaust victims and survivors. I learned from Sabine many things I did not know, particularly about Paula and Gerda, two sisters of my father who arrived in Hamburg after being expelled from Bad-Harzburg upon the sale of the family’s store.

The two sisters rented a small basement flat and made their living from sewing and occasional jobs. Sabine obtained documents that showed that the money they had (several tens of thousands of Deutsch Marks) was confiscated by the government and that they had been required to file a monthly “subsistence budget” to a trustee acting on behalf of the German treasury. Only upon the treasury’s approval could they receive that money. Sabine also gave me a copy of a “resident certificate” in a concentration camp where Paula Boas was. She succeeded in tracing documents showing that the two sisters had met with their mother, their sister, Marga, and her children, Ruth and Zvi, in the Ghetto Lodz, and that the mother had passed away there. She also found the original minutes of the auction of the personal belongings of my father’s two sisters after they had been sent from their flat in Hamburg to the Ghetto. The minutes declare that the money of the sale was designated to help Germany’s war efforts. Sabine continued to amaze me by obtaining more documents of my father’s sisters from the time they lived in Hamburg. For example, she located their ship ticket to London, which one of them managed to obtain in August 1939. She, however, decided not to use the ticket, but, rather, waited for her sister. Their wait, thus, decided their fate, since the war broke out a month later.

Sabine was part of a volunteer group that works to commemorate the Jewish families that lived in pre-war Hamburg. One of their best-known projects is “Stumbling Stones” (Stolpersteine), which was conceived by German artist Gunter Demnig. The “stones“ are small metal plates embedded in the sidewalk next to the houses of Holocaust victims across Germany. The plate lists the victims‘names, birthdates and expulsion dates. My two aunts have been commemorated in this project too, creating the link between me and my family from Bad Harzburg.

STARTING OVER

In February 2011, the volunteer group published a book about the Jewish families of the Eppendorf quarter of Hamburg. The publication was marked with a seminar to which I was invited to speak on behalf of Holocaust victims’ families. I told the German audience about “the life of an Israeli family in between Holocaust and Resurrection,” the impact of the Holocaust on the daily life in Israel, our silence and the Holocaust suppression complex and the agonizing uncertainty of not knowing how your family members died.

The Cultural Center in Hamburg was packed: people crowded the aisles and some even sat at the edge of the stage. I spoke in German. No one interfered with the harsh things I said about the Holocaust and living in its shadow. The audience was very attentive, and I did not need to resort to the comments I had prepared in advance in case someone in the audience would interrupt.

Today, the Holocaust bears additional significance for me. Family members that I have never known are suddenly close to me, thanks to Rosie Schwartz, Kurt Neumann and Sabine Brunotte.

On my personal Holocaust memorial day, I empathize with the fate of my family, which was expelled from their home and murdered with devious cruelty. Never before was I able to identify with them the way I do today.

On my personal Holocaust Memorial Day, I salute the realism of my father and his brother, who relinquished the luxuries of a well-to-do family and were not fooled into believing in the “enlightenment of the German people.” Instead, they chose to start a new life in Eretz Yisrael, which turned into the State of Israel. On my personal Holocaust Memorial Day, I try to find comfort in having affixed a memorial plaque to the wall of my fathers’ family house in Bad Harzburg, and in the many moving comments I received from passersby who read the short history of my family there.

On my personal Holocaust Memorial Day, I remember with great satisfaction how I stood in front of a German audience in Hamburg and told the people what I think about their responsibility of the atrocities of the Holocaust. A large photograph of my family and my father was projected onto the wall behind me, as if they were standing by me on the podium. This may not be a big victory, but it is the least I could do for my family, which was murdered in the Holocaust. And, it was an important way to honor my late father. For me, this is a lot.

David Boas had served as the budget commissioner in Israel’s Ministry of Finance. Today, he serves as the chairman of the Israeli Film Fund.